Author: Paula Kane

John and Lucine O’Brien Marous Chair of Catholic Studies, Department of Religious Studies

In a year that honored Fred Rogers as an exemplar of Pittsburgh and progressive Presbyterianism, the current show at the Warhol Museum embraced a more complex native son and his oblique connection to Catholic traditions.

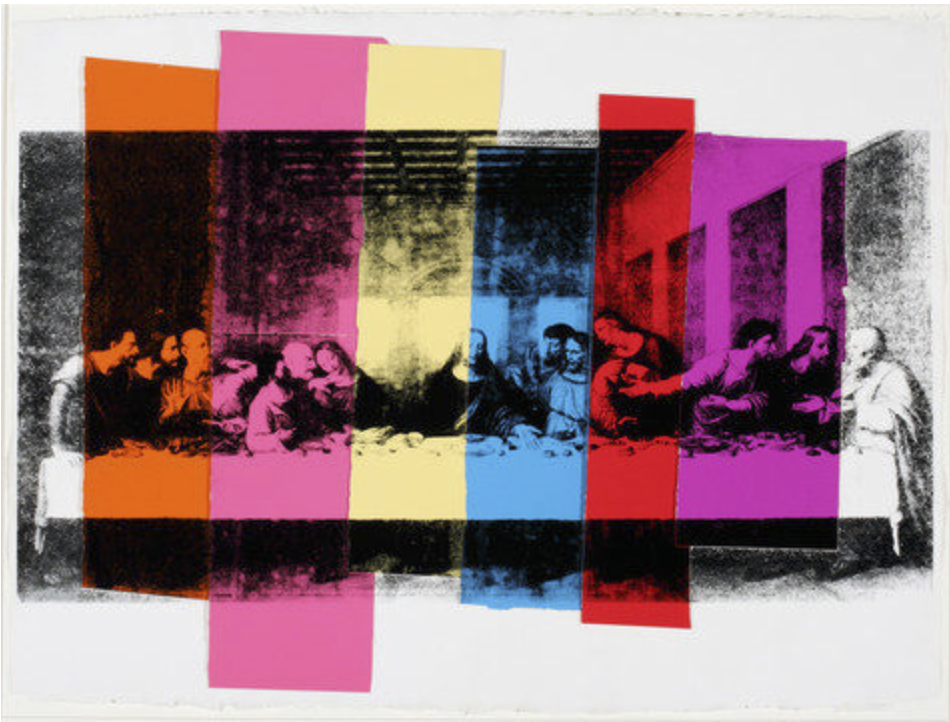

For the last several years I have worked with the Andy Warhol Museum as an advisor to its current exhibition, Andy Warhol: Revelation. The show is the first to highlight the artist’s religious background and influences. It closes in Pittsburgh on February 16 and will travel to the Speed Museum in Louisville, Kentucky, and then to the Brooklyn Museum of Art. The five rooms of the exhibit are preceded by Sunset, an unusual Warhol film from 1967 as part of a commissioned project for the Vatican pavilion at the 1968 world’s fair in San Antonio. Although the project was never realized, Warhol’s 33-minute shot of a California sunset hints at his anxieties about death and disasters–themes that consumed him in the 1960s–, as well as the spiritual sublime. Sunsets may be passages into darkness, or gateways to the dawn. The show then opens with “Ruska Dolina: Church & Community,” depicting Warhol’s local religious influences. “Glory & Graces” connects the tradition of sacred icons of his Pittsburgh parish to his well-known secular icons, Marilyn Monroe and Jackie Kennedy. “The Catholic Body and The Renaissance Spirit: Inspiration from Leonardo da Vinci” consider the role of the body in Warhol’s art and his engagement with sacred Renaissance painting. The final segment, “Sacred & Secular: Reproductions and the Imitations of Christ,” matches artworks drawn from elite sources, such as Raphael Madonnas and da Vinci’s Last Supper, with mass-marketed items like Jesus night lights.

In addition to Warhol’s own works, a variety of items enhance the exhibition: drawings of angels by the artist’s mother, who lived with him in New York; Catholic kitsch garnered from city flea markets; photographs of Warhol with friends and the pope; newspaper ads and clippings that Warhol used in his silkscreens; line drawings of body parts. Since this exhibition is the first to highlight Warhol’s Byzantine Catholic roots, it offered an ideal opportunity to consider religion in the life of a modern artist. A conversational approach to this topic seemed more fruitful than a lecture, so I invited art historian Erika Doss from Notre Dame to join me at the museum a few weeks ago for the evening event, which we accompanied with projected images.

What does revelation mean for a modern artist? For Christians, the word has its roots in the cryptic final book of the Christian Bible, where the end-time is vividly depicted. It speaks of a world undergoing a series of crises before being transformed by the victorious redemptive work of God. For Andy, did a sense of revelation play a part in his life and his art? What does he reveal to us, his viewers? Our conversation at the Warhol hoped to reveal at least two things: first, that in the art world, the religious identity of Warhol was more challenging than his gay identity. As performance artist and poet John Giorno recalled, it was far worse to be religious than gay. It was hard for modernists to accept that religion still mattered. Our second revelation, therefore: Warhol was both religious AND modern.

Warhol was surrounded at The Factory, his studio from 1962 to 1984, by a cohort of “lost boys,” mostly lapsed ethnic Catholics from working-class families who were constant reminders of that shared religious heritage. Andy was religious, though in an idiosyncratic fashion. In Pittsburgh, his family had moved to Dawson Street in Oakland to live near their church. In Manhattan, Julia Warhol continued to attend a Byzantine rite church, while her son went to Mass at least weekly at various Catholic parishes, rarely taking the sacrament of communion. Andy often stayed at services only for ten minutes or so. We can only speculate about whether he feared the Church’s condemnations of homosexuality, or lacked a spiritual connection with the sacrament, or just liked to watch the congregations without being observed himself. He customarily carried a rosary and a missal with him, and his townhouse was full of devotional objects. He was proud of meeting Pope John Paul II in 1980.

Although not “a religious artist,” Warhol was both religious AND modern. He made hundreds of prints of religious subjects, but especially in the two years before his death, when he repeatedly focused on da Vinci’s Last Supper, using a German engraving of the painting. Here, Warhol’s production of copies of copies of copies using modern photo or print technology and overlaying it with camouflage or pink paint recalls the role of sacred images and relics in Catholic culture: there, the power of the object is not diminished by copying, in contrast to Walter Benjamin’s famous claim that the aura of the original could not be replicated. In Catholic belief, the copied item (a vial of holy water from faraway Lourdes, for example, or a blessed holy card) still carries its sacrality, and the portability of holiness is an important aspect of devotional culture.

The exhibition segments on the Last Supper and the Catholic body remind us of the important role of devotions in Catholic practice and of the incarnational core of Christian faith: material objects that can be touched, smelled, tasted, and admired visually are reminders of the presence of God, who took on human form. Andy grew up during the heyday of devotional Catholicism in the U.S., and appreciated its “thingness,” often for purposes of parody and satire, which led him suggest tantalizing connections between the Catholic subjects of the great Renaissance artists and the cheap mass-marketed religious items of the present.